ORDNANCE SURVEY

Top of Page Href

Ordnance Survey Maps

Including separate sections for

I haven’t covered the Ordnance Survey 10 mile to an inch road maps, as by the time these appeared cyclists would no longer be using maps on such a small scale.

OS One-inch First Edition (including New Series) Click here

OS One-inch Second and Subsequent Editions Click here

The Demise of the One-inch Map and Birth of the Landranger Click here

OS Half-inch Scale Maps Click here

OS Quarter-inch Scale Maps Click here

OS 1:25,000 Maps(Explorer/Outdoor Leisure) Click here

Although the OS never produced specific ‘cycling’ maps, as by far the primary surveyors and cartographers of the nineteenth century their work ended up, acknowledged or not, in all privately-produced maps. As a result, some introductory notes on the general progress of the Survey are apposite, before turning to the Ordnance Survey’s own products.

The roots of the survey go back to the end of the 18th century, when the need for an accurate map of Britain was identified for military and defensive purposes. A map on the scale of one inch to a mile was decided upon, but the first priority was the establishment of accurate latitude and longitude coordinates of a number of base stations, achieved by triangulation, from which secondary and tertiary triangulation could establish further points as locally as desired. Thus, even before the one-inch map itself appeared (in some cases decades before), triangulation information supplied gratis by the Ordnance Survey was adopted by private map producers to improve the accuracy of their own maps, or in the creation of new maps, many of which remained on sale well into the cycling era.

Until the end of the 19th century the one-inch map was THE Ordnance Map as it produced nothing on a smaller scale for general public use. Cyclists have always used the one-inch maps, the only thing against them is (or rather was) that in nearly all cases the rider could obtain all the information needed on a map of two, three or four miles to the inch, and so covering a much greater area, so apart from the early days of cycling when such rival maps were of poor quality, or from the 1960s onwards where main roads have become progressively less attractive, the one-inch map was not the automatic choice. The scale of one inch to a mile is 1:63,360, or slightly less than its modern counterpart and successor, the 1:50,000 Landranger map.

It was not until the start of the 20th century that the Ordnance Survey produced smaller-scale reductions from its 1” maps, such as were proving popular with cyclists and marketed by commercial publishers. All the relevant productions are described following, classified by scale. Where I have quoted prices these are for the folded versions, either plain paper or mounted on cloth, as these would be the ones used by cyclists.

Href1

OS One-inch Maps First Edition (including New Series)

The first map in an intended coverage of Great Britain was a county map of Kent, produced in 1801, on the scale on one mile to an inch (1:63,360), reduced from a base survey at two inches to the mile. Map production gradually proceeded northwards and from 1840 it was decided to undertake the remaining base survey at six inches to the mile (already adopted for Ireland). By this time the publication of the one-inch map of England and Wales had proceeded north to the Preston – Hull line (Sheets 1 to 90). By 1869 the remainder of northern England had been published, with finally the Isle of Man in 1873 (sheets 91 – 110). Scotland was handled separately: the one-inch Scottish First Edition one-inch maps were published between 1856 and 1887, although survey work on the six-inch (or larger) scales was completed in 1882. Ireland was completed in 205 sheets. The terms 'First Edition' or 'Old Series' were of course only applied retrospectively.

This ‘First Edition’ was subject to periodic revision, but this mainly comprised the addition of railways and other major civil engineering works, urban growth being omitted, though the OS were also separately producing town maps and other larger-scale maps to cover such areas. Having started as a branch of the military to produce maps for the defence of England, it was now producing maps over a wide range of scales for purposes such as public health, land ownership and agricultural taxes. Most of its attention was therefore concentrated on the six-inch and 25-inch surveys, and bespoke maps for public clients. Like these larger-scale maps, the one-inch map was treated as a specialised product, and not marketed toward the wider consumer base it could potentially have served, while maps on scales smaller than the one-inch seem to have been regarded as not ‘proper maps’ and so were left to commercial publishers – their so-called ‘reduced' ordnance maps. However, with the spread of cycling and travel generally, a new and highly profitable market was growing up for such maps, while these maps were increasingly dependent on the Ordnance Survey for detail.

This is probably the best place to comment on some issues concerning the depiction of routes acceptable to cyclists, as these reduced maps only reproduced what the Ordnance Survey showed.

It may be said that the First Edition one-inch maps did not show footpaths, in that for any track to be shown it had to have some physical identity on the ground, rather than that it merely conformed to the legal status of a right of way – it was a military survey after all, and unconcerned with such niceties. On the larger-scale maps from which the one-inch was derived a track might be marked as a footpath or bridleway, but these were based on apparent usage rather than any legal authority. As a result, the lowest designation of such tracks and paths as made it onto the one-inch maps was usually a thin double line, as used for minor roads. The use of a single dashed line to indicate a ‘path’, still to be seen where not superseded by right-of-way status (and hence ubiquitous in Scotland) was very sparingly used. These shortcomings were later recognised, as an officer of the survey wrote in 1886:

”We have recently endeavoured to meet an often expressed want in the Ordnance one-inch map, by separating roads for wheeled traffic into three categories, main and turnpike roads, ordinary metalled roads, and minor roads (including carriage-drives and cart-roads), and giving each its distinct characteristic representation on the map, either by a thickened line on one side or by a difference in the width of the road on the paper . . . it is hoped that these additions will be recognised as an improvement, and satisfactorily meet objections that have been raised by the driving public.”

The routes so marked on the Ordnance Survey were naturally copied over onto the maps reduced from it, published from the middle of the 19th century. As a result, publishers such as John Bartholomew and W. & A.K. Johnston displayed many tracks unsuitable for cycling, particularly on their Scottish maps, alongside what were roads in the nowadays-accepted sense, that of ‘a way fit for wheeled vehicles’ (and most people would add ‘with an engine, at least four wheels and a horn’). The later OS one-inch maps from the 1890s introduced a ‘path’ status: this was quickly adopted by Bartholomew, but other publishers were still showing these paths as roads well into the motoring era. I have gleefully pointed out some of the more egregious examples under the names of the respective publishers, though some of the blame, if blame there be, must be laid on the Ordnance Survey, for not being more discriminatory on the tracks it initially had indicated. However, it should be said that very few cyclists of the time would have ventured off what were recognisably main roads once away from their home patch.

Unless the Government is prepared to place maps on the market in the same form as other publishers the public must suffer. The price of official maps is almost prohibitive, while the forms in which they are usually issued are highly inconvenient. Another objection is that they are difficult to be had, for no bookseller would be foolish enough to keep them. Thus it is that great good has been done by geographical publishers who have incorporated the results of Government surveys in maps that are adapted to the public taste and convenience.

Href2

OS One-Inch Maps Second and Subsequent Editions

The Committee are of opinion that the evidence which they received showed that there would be a considerable sale for a coloured edition of the 1-inch map; a thin paper edition of the 1-inch map, arranged to fold in a case; combined maps, where the centre of interest ordinarily appears on the margin or corner of a sheet, on the lines of a few which have been already issued; and a small scale map for cyclists.

The Third Edition one-inch map appeared between 1903 and 1913. Black and white map versions were based on the boundaries of the 350-odd small-sized earlier sheets but were newly engraved; new coloured sheets, lithographed from these and generally incorporating two sheets, were also produced. From 1905 most sheets were issued in a larger size, by combining two previous sheets. The new prices were initially 1/6 paper, 2/- mounted on cloth, though the latter was to increase to 3/- at the start of WW1. Over fifty special sheets, of larger size but more limited colouring, were on sale by 1915. The one-inch map was now more competitively priced and with larger sheet areas to compete against rival small-scale maps. But it was only after the First World War that the OS really satisfied consumer demand with better marketing, attractive map covers, multiple colours and special maps to cover tourist areas for its one-inch and new half-inch maps.

Ireland, as yet unpartitioned, was covered in 205 one-inch sheets, available in outline (most with contours) or coloured without contours. Sheets were 18” by 24” size, priced 1/- folded, 1/6 on cloth. After 1922 covers of those published for the Irish Free State in Dublin displayed the Irish harp in place of the royal coat of arms. A Third Edition on larger sheets followed those for England and Wales, and Scotland.

The Third Edition was superseded by the Popular Edition, which appeared between 1918 and 1926, though this was based on updating the earlier plates – ‘since, owing to the War, the issue of the revision was getting behindhand, it was necessary to get out a map that would not involve the preparation of elaborate plates, with consequent delay’ (Col. Sir Charles Close: The Map of England, 1932). It was thus basically the Third Edition of only a few years before, and was initially viewed as an updated version of it: in time the Popular Edition became the de facto Fourth Edition but was never referred to as such (a few sheets of a true Fourth Edition of updated mapping had appeared before WW1). The rather unnecessary hill hachuring of the previous maps was abandoned, it finally being accepted that Joe Public did understand contours, and – of most importance to cyclists – the maps gave more detail on road conditions. A further popular move was that the England & Wales sheets were, at 2/6 mounted on cloth, sixpence less than their predecessors. This was held until the start of WW2. Paper versions were 1/6d, increased to 1/9 around 1930. A feature unique to the E. & W. Popular Edition was that the sheet titles were introduced as ‘Contoured Road Map of ̶̶ ̶̶̶̶ ', a distinction never used before or since. True, there was ample road information, but it was still the standard one-inch map and the ‘Road’ description would have been more suited to smaller-scale productions.

The companion Scottish sheets of the Popular Edition appeared between 1925 and 1931. These were slightly larger (28” by 19”) to provide some overlap, and some stylistic changes were made to improve clarity compared to the England & Wales format, and the two series now shared a common projection. ‘The substitution of modern methods of photographic reproduction for the former process of engraving on copper has made it possible to improve the character of the map and at the same time produce the sheets more quickly’. Scottish sheets were initially priced at 2/- on paper, 3/- on cloth (“mounted” in OS parlance), though about 1933 a reduction to 2/6d was made for the latter. In all there were 92 sheets, four of which straddled the English border. Scottish sheets 86 and 89 duplicated the England & Wales sheets 3 and 5 respectively.

From 1919 the England & Wales Popular Edition map covers showed a picture of a seated cyclist inspecting a map; from 1933 this was replaced by a seated walker. Scottish maps showed the Scottish Coat of Arms. Both series were supplemented with numerous ‘District’ and ‘Tourist’ maps. A curious feature of the Popular series (and the contemporary half-inch maps) was that the cover of the cloth-mounted map made no reference to its format, only the dissected version having its status quoted alongside the price. From some publicity you would not know there was a paper version. Yet from 1967 the cloth-backed format was to be discontinued by the Ordnance Survey.

From 1930 onwards the Ordnance Survey made many of its small-scale maps available on Place’s Waterproof Paper Paper – ‘This material is not merely ordinary paper coated with a waterproof solution but is specially manufactured and impregnated after printing by a process which renders it absolutely waterproof and washable and gives it a parchment-like toughness and durability’. Initial prices for these maps were 3/6d for the Popular Edition maps, 4s for the Tourist maps It seems to have been more successful than the Pegamoid waterproof maps of thirty years earlier produced by various commercial publishers, but was dropped around 1935.

Hitherto the One-Inch Maps of England and Wales have been based on engraved copper plates. At each revision these plates were duplicated and corrected and the One-Inch Maps were produced by transferring the engraved outline to stone and zinc. Engraving has now been abolished and the new map is being drawn for reproduction by the photographic process known as Zinco-Heliography

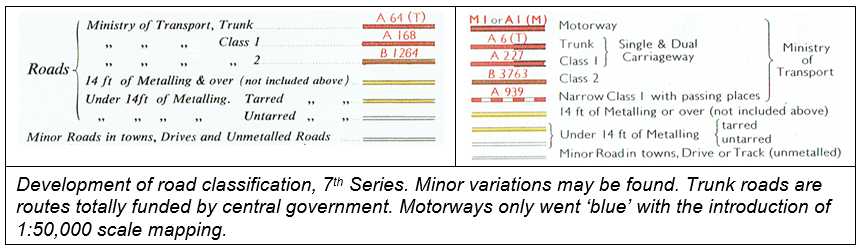

The Fifth Series was produced in two formats; with and without relief shading (red and blue covers respectively). Completion was expected to take fifteen years but by the start of World War 2 only partial coverage of southern England had been produced, and further production ceased. The sheet numbering initially retained that of the Popular Edition, though boundaries were far from identical, the sheets now being linked to an imperial-unit national grid and covering 52,000 yards by 32,000 yards (29.3 miles by 18.1 miles). Later sheets covering south-central England were larger, and on a new numbering system, but WW2 put an abrupt end to production.Whereas the pre-war Popular Edition never showed road numbers, these were shown from the outset on the Fifth Edition sheets, with the following comment added to the key:

Note: Differences of Road Classification, where they exist between the Ordnance Survey and Ministry of Transport are due to the fact that the former is based on examination on the ground while the latter has more particular regard to the traffic value of the road as a means of through communication.

The old roads, and many of the earlier arterial roads, are very congested with traffic, traffic lights, cobblestones, stationary vehicles and shoppers, but the modern arterial roads give for the most part good surfaces, plenty of room, roundabouts instead of traffic lights and rather pleasanter scenery in the way of roadside buildings.

Remember, roundabouts at this date had no ‘give way’ rule: cyclists were expected to ‘weave’ in and out of other traffic. Amongst the recommended routes in and out of London in the handbook were Western Avenue, Hendon Way and the Kingston Bypass; and for bypassing central London the North Circular Road. A different era indeed.

Throughout its period of production in addition to the numbered national sheets of the one-inch map there were also numerous ‘District’ or ‘Special’ sheets, covering areas otherwise inconveniently split between a number of sheets. After WW1 these had been supplemented by a number of Tourist Maps, which usually featured contour-colouring and other style differences. The special sheets did not appear after WW2 but several Tourist maps were reissued alongside the 7th Series.

Rights of Way were added to the one-inch map of England and Wales from the 1960s, although as not all Local Authorities had then produced Definitive Maps coverage was patchy for many years. For cyclists of the time, its main benefit was to identify those ‘white’ (untarred) roads over which some rights of way existed, and bridleways, which common sense would suggest should be available (if not necessarily practical) for cyclists It is worth mentioning that compiling this Rights of Way information is the responsibility of local authorities, not the Ordnance Survey, who are obliged to show it as supplied. Thus if a Right of Way is severed by a new dual carriageway, the map will show it right up to the sides even if no crossing point is provided. A Right of Way need not have any physical identity, best illustrated by those over the shifting sands of Morecambe Bay. Even where a Right of Way exists and is thus shown, its use may be restricted, or even prohibited, if crossing MoD land. In 1968 the long-claimed right of cyclists to use bridleways was formally recognised in legislation, which perhaps encouraged cyclists to invest in the OS product at the expense of other small-scale maps. Rights of Way have never appeared on the equivalent maps of Scotland and Ireland.

Href3

The Demise of the One-Inch Map and Birth of the Landranger

In the 1970s the one-inch scale was replaced by the 1:50,000 scale series, later branded ‘Landranger’, still going strong today. Although a few of the old 1” Tourist Maps were perpetuated (using new 1:50,000 mapping reduced to 1:63,360) and two new sheets were added all had been withdrawn from the OS catalogue by 1998.

After ignoring cycling entirely, in 1998 the OS was persuaded to add cycling information to its 1:50,000 maps. This was the denotation of National and Regional cycling routes by a series of green blobs, where on-road, and giving route numbers. Off-road sections were indicated by green dashes. Whilst a start, this did not help cyclists appreciably, because on main roads it gave no idea of whether the ‘cycle route’ was merely a route number or implied some segregated facility. This uncertainty would deter some riders from risking the route. Around 2008 the marking was changed, to indicate cycle facilities: a hollow green blob for traffic-free sections and solid green blob for on-carriageway sections. These were applied to a wider range of locations.

Old OS one-inch maps, from the First Edition through to the 1950s Seventh Series, are widely available for viewing on the internet, and certain editions have been reissued as paper copies.

Href4

OS Half-inch Scale Maps (1:126,720)

The first OS half-inch mapping, though not intended for general sale, had been produced as indexes to the large-scale maps such as the 1:2,500 series or for administrative purposes. These maps were county-based and date from around the 1870s or 1880s. They were fully detailed, but no general version of them seems to have been offered to the public, though they could have formed the basis of some excellent cycling maps just when they were first needed.

Not until 1903 – just as Bartholomew were completing their half-inch coverage of England and Wales, having long covered Scotland -- did the Ordnance Survey begin to issue its own general-purpose maps on that scale, based on the recent one-inch map revision. In general the sheets boundaries corresponded to the areas of four one-inch sheets, and revision was tied to the updating of those sheets. Initial size was thus only 12” by 18”, but when the OS 1” sheet sizes were enlarged (to 27” by 18”, 24” by 18” Scotland) the half-inch size was similarly increased. National coverage was completed in 1910.

These maps were available in various formats such as with or without hill shading, now applied more discreetly and in a tone of brown. From 1906, rather strong contour-colouring (termed ‘layering’ by the OS) replaced hachuring, though an unlayered version was also issued. In terms of price and map size the OS maps were now a good match for Bartholomew. Despite this and the authority of the Ordnance Survey they never acquired the popularity of the Bartholomew maps. Sheet size was similar (England & Wales in 40 sheets compared to Bartholomew’s 37, Scotland 34 against 29). Prices, pre-WW1, at 1/- paper, 2/- on cloth, were the same, although the CTC offered a discount on Bartholomew maps. Perhaps Bartholomew maps were available in more outlets: in any case, judging by the relative number of old copies turning up in second-hand bookshops or on the net, they considerably outsold their OS rivals.

In addition to the numbered series, special sheets were advertised in the 1920s for Salisbury Plain, Aldershot (these two probably reflecting military needs), New Forest, Birmingham, and Loch Fyne & Loch Lomond. These dated back to the period of the small-sheet series, when they better complemented the numbered sheets: when some new special sheets were produced in the 1930s only the Birmingham title was revived.

In 1923 the OS produced a set of half-inch maps for the Ministry of Transport, as a visual index to the new classified road network on an uncoloured base. The sheets boundaries and numbers were the same as the regular half-inch series. The intention was that the maps would be periodically updated as the network developed, though few reissues were in fact produced. These maps were intended primarily for the use of local authorities and others, rather than road users, since until such numbering appeared on direction signs they were of little use to the latter and, initially, did not necessarily reflect the quality of the roads themselves. Although other map publishers were quick to add the new road numbers, the OS never showed these on its general half-inch scale maps, which can’t have helped their sales. In that respect, the MoT editions were probably of more use to motorists than were the standard maps, despite the loss of contours and information on minor roads. Cyclists would gain nothing from them.

Coverage of England, Wales and Scotland in the MoT series, as well as a later outline version of the standard half-inch map, is now available on the National Library of Scotland website.

Roads 1st Class – ‘Good and fit for fast traffic’ (continuous red)

Roads 2nd Class – ‘Fit for ordinary traffic’ (continuous yellow)

‘’ ‘’ “ – ‘Indifferent or winding’ (dashed yellow; ‘chequered’ in OS parlance)

Other roads (uncoloured)

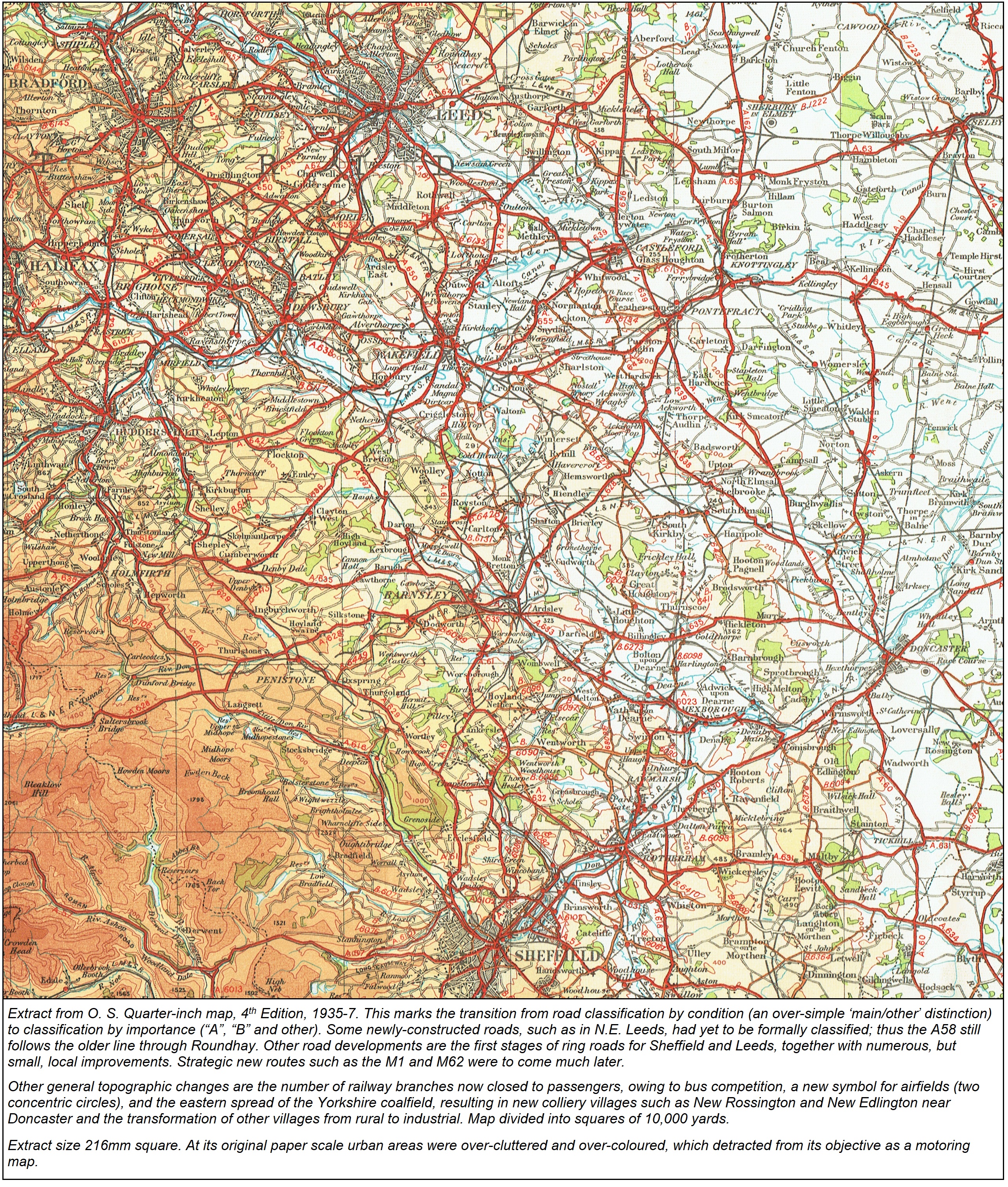

From 1935 the map key was changed to reflect the new one-inch map road classifications, with red reserved for MoT Class “A” roads, yellow for ‘Other motor roads’ (including “B” roads) in two widths; there was a ‘Bad’ motor road category (broad uncoloured) and narrow uncoloured for ‘minor roads’. However, most sheets were never revised to show these new classifications, and as mentioned none showed the actual numbers. Updating was discontinued with the outbreak of WW2.

In the 1930s the Ordnance Survey produced some special sheets, covering very broad areas. These were in the style of the OS one-inch 5th edition, though based on the Popular Edition map. Six sheets were produced:

- Cotswolds (1931)

- Birmingham (1933)

- Chilterns (1935)

- Greater London (1935) (possibly earlier editions exist in older style)

- Peak District (1936)

- Isle of Skye & District (1937)

Unlike the normal half-inch series, all these maps actually displayed MoT road numbers. Apart from this, they had a variety of road categorisations, not all particularly useful to cyclists. For example, the Peak District map (at least in some issues), left uncoloured all roads below the category of “B” road, giving pot luck to users as to whether these were tarred or not. By contrast, the Greater London map - described by Kuklos (W. Fitzwater Wray) as ‘the finest map I have ever seen, either of our own or any other country’ - left all unclassified roads uncoloured, but divided them into wide, narrow and unmetalled.

The justification for some of the special sheets seems dubious, but exception must be made for the Greater London and the very beautiful Isle of Skye maps, which provided unified coverage over specific areas which would otherwise require numerous one-inch maps and which were split between the serial half-inch maps.

Work on a Second Series of half-inch maps was begun just before the Second World War, but the plates on which the new OS mapping was based were destroyed in bombing raids, along with those for the pre-war Series. Only the plates for the 1935 London Area map survived destruction.

The production of a new national Second Series of half-inch maps was started afresh in the 1950s. Scotland, Isle of Man, England and Wales were to be covered in a series of 51 projected sheets (compared to Bartholomew’s 62). The first sheet produced, in 1956, was Canterbury (‘provisional edition’) covering most of Kent. Cover styles replicated those of the contemporary 7th Series one-inch maps but in green rather than red. Prices c. 1960 were 5/6d paper, 7/6d cloth, compared to 3/- and 5/- respectively for the equivalent Bartholomew maps: a big price differential despite offering a larger sheet size and a more thoroughly updated map. As first published, the OS do not seem to have decided whom the series was intended for, as it included many ‘white’ roads unsuitable for (most) motor vehicles: the Snowdon sheet being particularly revealing in its choice. Most such untarred roads were excised from such later editions that appeared.

Sales were poor and only five sheets were published - 43 Greater London (1962), 51 Canterbury (1956), 39 Norwich (1961), 36 Birmingham (1958) and 28 Snowdon (1961) before the project, deemed as low priority, was abandoned. The Greater London sheet never bore its intended number but appeared as Greater London Half-Inch District Map, the District title then being applied to the other sheets, cover styles now emulating those of the one-inch tourist maps. The last of the series to survive was Snowdon, reissued in 1966 with extended area and retitled the Snowdonia National Park tourist map (not to be confused with a bloated Routemaster-based sheet of the same name).

Ordnance Survey half-inch maps of Ireland appeared from around 1902 onwards, contemporary with those for Great Britain, although less than half had been completed by the start of WW1. There were in all 25 sheets, 27” by 18”, in layered or unlayered formats. The earlier sheets indicated both First- and Second- Class roads in brown, distinguished only by width (on the map) whereas the later sheets to appear used a dashed brown for secondary roads and subdivided uncoloured roads (again by width) into tertiary and other. However, the older style was not superseded until the 1950s. Later, division by road numbering was introduced. In the Republic this map series (taken over by the Dublin-based Ordnance Survey from 1922) lingered on until the 1980s, rivalling Bartholomew maps for underlying antiquity.

These maps were also continued by the Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland in Belfast until an OS Second Series of four larger maps, covering the province, appeared in the 1960s. On these, roads were divided into “A”, “B” & “C” (Unclassified but well surfaced), and Other, with their equivalents in the Republic. These maps were not perpetuated and an announced 1990s replacement at 1:100,000 never appeared.

Href5

OS Quarter-inch Maps (1:253,440/1:250,000)

The Ordnance Survey quarter-inch maps of Great Britain qualify for this treatise as ‘maps for the cyclist’ rather than ‘cycling maps’, at least for those editions before the growth in motor traffic rendered use of the main roads less acceptable. As an illustration, when touring in the 1960s I generally used a mix of OS quarter-inch and Bartholomew half-inch maps: as about two-thirds of my mileage was on “A” roads (not unusual for the period) the former scale was perfectly adequate. It was also necessary to cycle from home to one’s chosen touring area, rather than stick the bike on a roof rack to skip the boring bits.

The first quarter-inch maps produced by the Ordnance Survey were ‘Index’ maps, acting as a key to the boundaries of the one-inch sheets, for defining sanitation districts, and other administrative purposes . For example, in 1868 and later in 1885 a map base on this scale was produced for Boundary Commission maps for most areas of England and Wales, These index maps were uncoloured and roads are restricted to main routes only and topographical information limited to a few place names, so as not to obscure whichever information was to be overlaid. Railways were shown – but not stations. Thus although there was national mapping on the quarter-inch scale, it was not produced with expectation of public sale as a general-purpose map.

The first public-orientated series was released from 1891, in sheets about 20” by 24”, fifteen covering England & Wales, completed by 1892. These were in ‘outline’, i.e. uncoloured, and generally accepted as being produced ‘on the cheap’ and not always as accurate or up-to-date as they should be – in fact they must be the worst maps ever produced by the Ordnance Survey. In substance they were the earlier ‘index’ maps, though with more detail added to the old engravings, which themselves had been based on rather outdated one-inch maps. Many main roads constructed in the 1830s and 1840s were omitted and the choice of minor roads displayed was somewhat arbitrary. Urban expansion since the production of the original survey was ignored: in South Wales the town of Maesteg, with a then population of 10,000, had no roads shown to it. Ancient routes across Salisbury Plain, little used even before the railways, were marked as main roads. An embarrassing omission was the Clifton Suspension Bridge of 1864, a useful link enabling cyclists to avoid the bustle and trams of Bristol. Railway companies and lines were named to the point of pedantry.

The maps were of course ‘general’ maps, rather than primarily ‘road maps’ and seem to have attracted little interest from cyclists, yet they were to have a curious new lease of life in the form of cycling maps published by G. W. Bacon - see under that firm. The 1894 O.S. catalogue includes a 15-sheet series of quarter-inch maps of England & Wales, with a similar series of 11 sheets for Scotland, both tucked away under ‘Miscellaneous Maps’. Prices were 2/- a sheet (22½” by 15”), uncoloured, no hill-shading or contours. Ireland was available on 4 sheets, 4/- each. By 1901 the catalogues were silent on these earlier editions, with reference only to the ongoing replacements for England and Wales, whilst Scotland and Ireland got no mention. Progress of the Irish maps is covered in a later section. Although clearly viewed as an interim series pending the availability of new one-inch source material, the 1890s maps were subject to some revision, primarily railways.

Unsurprisingly, this ‘interim’ England & Wales series does not appear to be viewable on the net (nor have I ever come across any hard copy), but the same base was used as background for a contemporary series of geological maps. This coverage can be viewed at Old Maps Online

Facsimiles of ‘Coloured Ordnance Survey Maps as published in 1897' were produced by Old House Books in 2005: these in fact were the elderly Bartholomew quarter-inch maps reissued that year with no relation to the contemporary OS maps on this scale. Similarly, a few years ago, the AA published a so-called ‘Illustrated Ordnance Survey Atlas of Victorian and Edwardian Britain’: this, however, used solely 1920s quarter-inch mapping, so neither Victorian nor Edwardian.

From 1899 (Scotland 1901) the O.S. Quarter-inch series was reissued with major revisions derived from the revised 1890s one-inch maps, whose sheet boundaries they followed. Place-names, topographical detail, railways etc were largely the same as before, but roads were thoroughly revised, particularly where the earlier sheets had relied on some of the more elderly one-inch mapping – the Devon area seems to have been completely re-engraved. There were now three categories of road, with ‘Third Class’ roads added as a single line. Additionally, a dashed line was used for some strategic tracks on the Scottish and Welsh sheets. Spot heights were introduced along roads on all but the 1899 sheets. Most sources treat these revised maps as the true O.S. Quarter-inch First Series, quietly disregarding the original c. 1890 productions.

A publicity release of 1901 stated:

The Ordnance Survey have completed the publication of the map of England and Wales on the scale of four miles to the inch. This is a general map of the country, and is likely to be useful to cyclists and others who require a considerable area of country on one sheet. It shows all the principal roads, railways, rivers, towns, villages, large woods, and, in addition, numerous altitudes. The map is published in 20 sheets, each measuring 22in. by 15in., at the price of 1s. 6d. per sheet, engraved. Another edition of this map is being prepared, the publication of which will shortly be completed, by counties or groups of counties, on thin paper, price 6d. per sheet, or 9d. if folded in a cover.

The sheet totals and their numbering need explaining, as various figures tend to be quoted. England and Wales were produced on 24 sheets (25 including the Scilly Isles), Scotland in 17. These sheets were based on a module of 5 by 5 one-inch sheet blocks for England & Wales (60 miles by 90), 3 by 3 of the larger one-inch maps for Scotland (54 miles by 72). As around the coast these blocks involved considerable areas of sea, a pragmatic approach was adopted whereby blocks or part-blocks were combined to produce more practical and saleable maps. Otherwise it would have taken three maps just to cover the Isle of Man. However, these sheets still had numbering taken from the 25 blocks, e.g. the single sheet Cornwall and Scillies being titled Sheet 21 and 25. In this way England and Wales were actually published on a more practical twenty sheets. Similarly, Shetland was available as a single sheet, Scotland 1 & 2.

The ‘County’ editions mentioned in the above press release, of various size and with main roads in sienna, were versions produced by lithograph transfers from the engraved numbered sheets. They were centred on and named by county or group of counties; for example one sheet covered the (then) six North Wales counties. A single sheet covered London and environs. The maps extended to the sheet margins, not county boundaries. Similar sheets in Scotland gave more practical coverage of Argyll and the Western Isles.

These maps were almost immediately complemented by what was at first termed the ‘Revised New Series’ appearing between 1902 and 1905, i.e. about the same time as the first O.S. half-inch maps. The underlying map was unchanged (apart from local revision) but an attractive 3D effect was introduced by delicate hill stippling, and colouring was employed for woodland. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, June 1902, was impressed:

These maps serve well to exemplify the very successful attempts that have been made during recent years to render the sheets of the Ordnance Survey of more general and popular service, and to print them in colours by which due prominence can be given to the physical features, roads, etc, without obscuring the lettering… The hill shading is shown in a manner which has not before been attempted by the Ordnance Survey - in stipple by photo-etching. No contour lines are given, but numerous altitudes are indicated in figures. One good feature of the maps, which will certainly be appreciated by cyclists, is the manner in which the roads are distinguished. First-class roads are shown by a double line and coloured, second-class roads by a double line and uncoloured, and third-class roads by a single line.

Only passenger-carrying railways were shown: it must have been disconcerting to the cyclist to come across a level crossing or bridge where, if his map-reading were correct, no railway should be. The 1:253,440 scale still enabled all minor roads to be shown outside of towns whilst allowing a greater area to be included on a single map than possible at larger scales.

Seamless Great Britain coverage of this series (both outline and coloured) may be found on the National Library of Scotland website, as can the Third and Fourth Editions. Most sheets (including the second series) may also be viewed individually.

Sheets titled Second Edition appeared from c.1909, though changes in style were confined to the introduction of a white circle for railway stations and not all sheets had been reissued by the time WW1 put revision on hold. The term ‘Edition’ was later to be used by the Ordnance Survey in a more restricted sense, to mark a substantial re-issue of a map series, such as new base mapping, sheet sizes etc rather than routine updates.

It was the unauthorised reproduction of this edition that led to the first prosecution on behalf of the Ordnance Survey under the 1911 Copyright Act (though resulting in just a token fine). In 1913 the London firm of H. G. Rowe & Co. had produced two threepenny sheets of a New Road Map for Cyclists and Motorists, which were lithographs from the current quarter-inch outline sheets of southern England with trifling alterations. The 'alterations' by Rowe had been the elimination of all spot heights and church symbols from the O.S. base – a laborious and rather pointless exercise, reducing rather than enhancing the value of the map – and the highlighting of a mixed bag of cycling roads. Although all copies and source plates of these maps were ordered to be destroyed, duplicate re-engraved but otherwise virtually identical versions were back on sale by Rowe in 1914. Rowe went on to produce a third map, covering Dorset, Somerset etc, which was clearly a manuscript reproduction of the OS quarter-inch map.

The England & Wales series was later (from 1913) reduced to ten larger sheets, using the same mapping as revised, and termed the Second Edition Large Sheet series. Pre-war prices were 1/6 paper, 2/- mounted on cloth.

|

These maps showed roads subdivided into only two classes, ‘Main Roads between Towns’ and ‘Other Metalled Roads’ (i.e. tar or waterbound macadam) - a retrograde step. As the maps were produced just before the MoT road classification system these road numbers could not be shown: indeed there was not too much correlation between the main roads as shown and the later “A” and “B” road network. An extreme example of a road classified as ‘minor’ is the present A66 trunk road between Scotch Corner and Bowes. The simple division of all roads into just two categories was ridiculously inadequate, and can be compared to the several categories used on the Bartholomew half- and quarter-inch maps, as well as the three on the previous OS edition. The old single-line used for the lowest category of road (‘Third Class’) was abandoned, roads either being upgraded to Second or simply dropped; as a result a great many minor roads previously shown and suitable for cyclists were omitted. Further shortcomings for cyclists were a lack of spot heights, making it very difficult to estimate the rise and fall of a road, and a 200ft contour interval, compared to 100ft for Bartholomew half-inch maps, admittedly, of course, on twice the scale. The competing Bartholomew quarter-inch maps always provided plenty of road spot heights.

Prices were 2/- for the paper edition (apparently available only as flat, unfolded), 3/- for the cloth mounted sheets, 4/- for mounted and dissected. Introduction of the series coincided with a policy of increased advertising of its range of maps by the Ordnance Survey .

In 1923 two of the main commercial rivals to the Ordnance Survey for small-scale maps, W. & A. K. Johnson and John Bartholomew, were complaining that ‘the map industry was seriously menaced by the Ordnance Survey Department issuing maps for motorists and tourists at prices which no private firm could compete with’. It is likely that they had the quarter-inch maps most in mind, as competing with Bartholomew’s rather-dated maps on the same scale and Johnston’s 3m to an inch series.

By 1927 some (not all) of the E & W sheet boundaries were revised, these new sheets initially being distinguished by an “A” suffix. The areas of these new and larger sheets were intended to be more convenient for the map user. These revisions resulted in the demise of Sheet 5, now covered by Sheets 4A and 6A which were later to lose their suffixes. Also dropped was the South Central England special sheet, mentioned above. Prices remained at 2/3d folded on paper, 3s on cloth, 4/- dissected on cloth. Scotland still had its separately-numbered series, now again of nine sheets (though Sheet 1 was also Sheet 1 of England), in which sheets 8 and 9 were later combined. In 1927 a ‘waterproof’ edition of the maps was on sale as a set of 88 sheets by one publisher. The Ordnance Survey was actually to reduce prices of its quarter-inch maps by 1928, with cloth maps 2/9d and paper 1/9d.

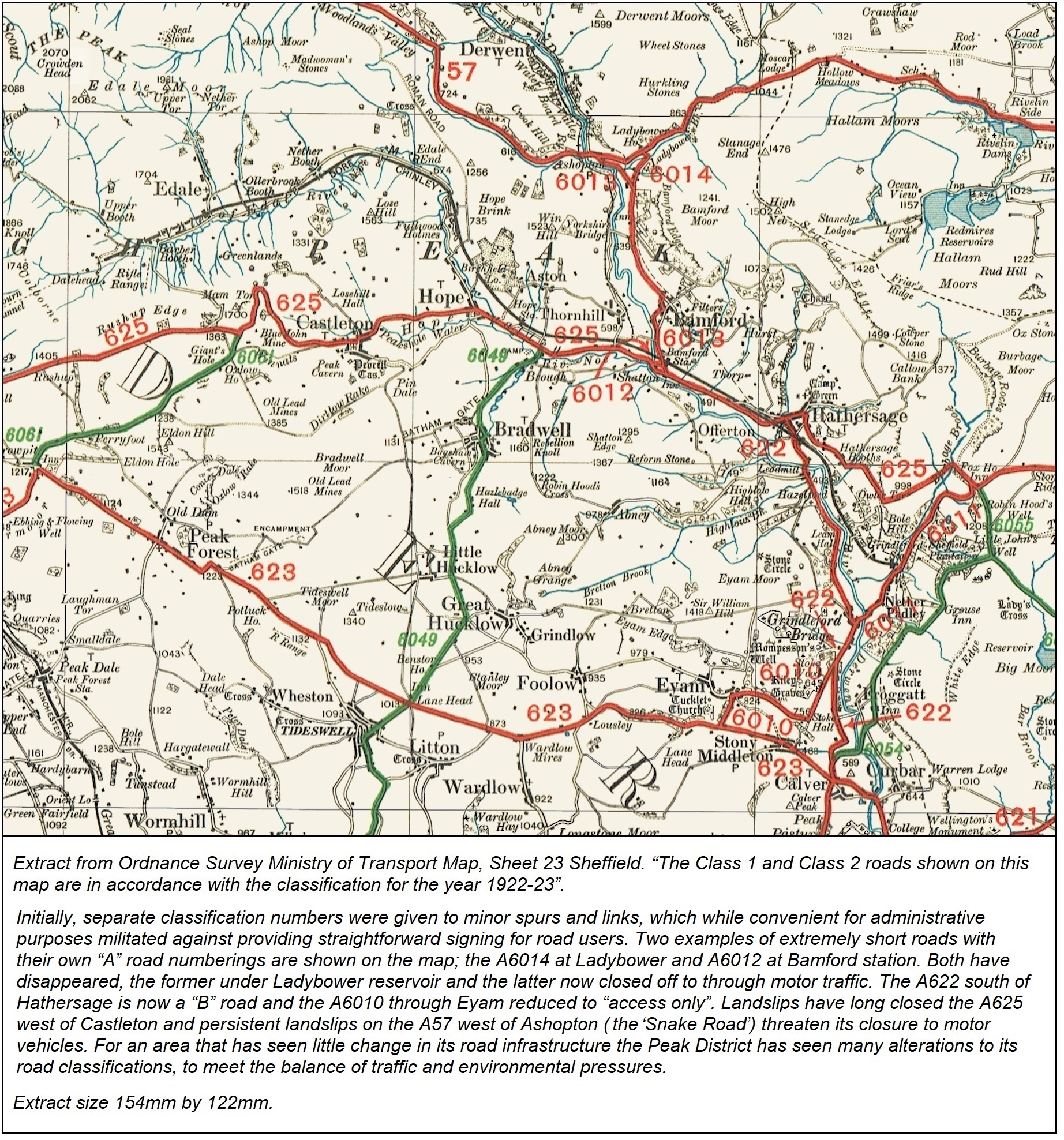

The Fourth Edition maps appeared in 1934-5 but initially used the same last full revision of the previous edition; the upgrade was more of cover style and size than a redrawn map. The sheets had a larger folded size difficult to fit into a saddlebag let alone a jacket pocket. Included with the maps was an insert pamphlet of town plans. Sheet prices went back up again. All maps now demarcated “A” and “B” roads, the latter now in brown. The few unclassified roads formerly shown in red were categorised as ‘Other Motoring Roads’ and initially remained at their previous width, though uncoloured: on revision these were ‘narrowed’ and placed in what was now described as the ‘Other metalled roads’ category along with the rest.

Post-war revisions included the addition of the National Grid at 10km intervals and the dropping of the cover picture of a motorist. The OS advertisement in the 1952 Kuklos Annual described the quarter-inch maps as ‘particularly useful to cyclists’: at this time they had no half-inch product to promote. Given the dropping from the map of much detail that would have benefited cyclists this claim was hardly true. During production of the Fourth Edition there was a tendency for minor roads to be dropped from the map upon revision, despite the overall programme of tarring such roads and other minor improvements. Some examples are given later.

The new post-war (1957) Fifth Edition, ‘metricated’ to 1:250,000 and with a smaller folded size more convenient for cyclists, brought a less cluttered style, mainly by omitting minor place names and urban detail. Of course, the projected OS half-inch series was expected to fill the gap between this and the one-inch map. A single series now covered England, Wales and Scotland. The heavy contour lines of previous editions were softened: indeed initially they were omitted altogether, only the colouring layers indicating height. However, the map now only showed tarred roads, and not metalled roads, omitting many well-used cycling routes. The omissions included such as the Tregaron – Abergwesyn road, which had rightly appeared on the Third Edition map. For the same reason all the hill routes from Lake Vyrnwy, to Bala and over the Bwlch-y-groes, were left off. These were well-established motoring as well as cycling routes, if a little adventurous, and leaving roads such as these off, together with the abandonment of road spot heights, rendered the map much less of a cyclist’s map than it should have been.

The following versions of the OS 1:250,000 maps – the Routemaster, later Travelmaster series - were unashamedly aimed at the motorist, with much minor road detail needed by the cyclist obscured by a plethora of road numbers, enlarged place names and tourist symbols. In 2016 these were replaced by two series – OS Road, which hark back more to the Fifth Series, and OS Tour, which consists of enlarged mapping swamped with tourist symbols. Although the latter are enlarged to ‘cycling’ scales these are not cycling maps. The number of other maps and atlases from other publishers available on these and similar scales is of course vast, but these cannot claim to be aimed at the cyclist.

The main historic interest today in the earlier OS quarter-inch map series is in what roads they deemed to be worthy of inclusion. As noted above, the Third and early Fourth Editions included some roads then still untarred, but these were hardly exceptional at the time and were probably in much better condition than they are now. These would have been passable by cyclists and motorcyclists, if not by all contemporary cars. Examples include

Rhayader – Cwmystwyth | Dropped from 4th Edition (1946 revision), restored in later 5th Edition as tarred road, its present status |

Llangurig – Cwmystwyth | Dropped from 4th Edition (1946 revision), never to reappear. Now NCR 818, untarred section all rideable |

Trawsfynydd - Llanuwchllyn/ Llanfachreth | Shown on 3rd & early 4th Editions; initially omitted from 5th but later shown tarred, its present status |

Halifax (Wainstalls) – Oxenhope | Now one central kilometre left untarred |

Lofthouse – Kirkby Malzeard | Now Byway status |

Todmorden (Lumbutts) – Cragg Vale | Shown on 3rd & 4th Editions (1946), omitted from 5th. Now public footpath! |

Kidstones Pass (B6160) – Stalling Busk (Stake Road) | Shown on 3rd & 4th Editions (1946), omitted from 5th. Remains untarred in its upper sections but easily rideable. |

After initially excluding all untarred roads, the later 5th series did relent and show a few examples, though the choice now seems very arbitrary. While some were eventually tarred and joined the ranks of motoring roads, e.g. the Borders road from Langholm eastwards to Newcastleton, others were and remain green roads, generally with vehicular restrictions, and shown in dashed lines. In the latter case fall

|

Head of Grwyne Fechan to A479, Black Mountains, SE Wales |

Now bridleway (Rhiw Trumau). Never more than green lane; should never have been shown. |

|

Pont Cynfyg (A5) – Dolwyddelan, Snowdonia |

Omitted from 3rd/4th editions until appearing as untarred route on 1975 5th Edition. Mainly gravel forest road. |

|

Salter Fell Road, Wray/Hornby - Slaidburn |

Omitted from 3rd/4th editions

until appearing as untarred route on 1973 5th Edition. Now much

cut-up in higher parts |

Just a word about maps. Phillips' [sic] "Six-penny Map of Ireland" will be found a very good one, and to a person acquainted with the course of the country is quite sufficient; but, together with it, I would advise the" Railway Commissioners' Map," of which each sheet contains one-sixth of Ireland, and has all the main roads marked, with distances from Dublin. The scale is quarter-inch, and the shading upon it will be found most useful. It is sold by Hodges, Forster, and Co., Grafton Street, Dublin; price, about 4s. 6d. a sheet.

In fact, the General Map to accompany the Report of the Railway Commissioners 1836 was still advertised in the OS catalogue of 1915, six sheets 3/4d each, alongside the later sheets described below.

An Ordnance Survey quarter-inch map of Ireland was published in 1887, in four large sheets, though pricey at 4/- each for an uncoloured map - “showing county and barony boundaries, rivers, railways, canals, leading roads, and principal demesnes”. Like the Great Britain equivalents, they suffered from being derived from what was becoming an outdated one-inch map. From a cycling point of view, their main interest lies in their being adapted by G. W. Bacon for that company’s cycling maps of Ireland from about 1900, as in the extract below, taken from what was named Ireland South-East on cover, South on map.

The two authorities now jointly produce a set of four largish maps covering Ireland. These are not cycle-friendly.

Href6

OS 1:25,000 Maps (Explorer/Outdoor Leisure)

Chronologically these come a distant last, as this scale of mapping was only introduced during WW2, initially for military and government use. A ‘provisional’ edition, based on these sheets, was made available to the public from 1946. However, it was never envisaged to be of much use to cyclists and even walkers were expected to favour the one-inch map.

Initial sheets were reductions from pre-war (and generally much older) 1:10,560 mapping and covered a single 10km National Grid square, the grid reference of which was used as the sheet naming system. There wasn’t a branch of W. H. Smith’s that didn’t have a sheet yellowing on its shelves, mis-ordered owing to someone confusing eastings and northings. Sales were limited and the series was nearly abandoned in the 1970s. However, larger-sized sheets and the gradual addition of Rights of Way assisted sales and from 1972 special sheets marketed as Outdoor Leisure Maps boosted their popularity. Coverage of the remainder of the country was branded initially as Pathfinder and later as Explorer sheets. They are now effectively a single series.

_______________________________________________

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20Waterford%20c1903.jpg)